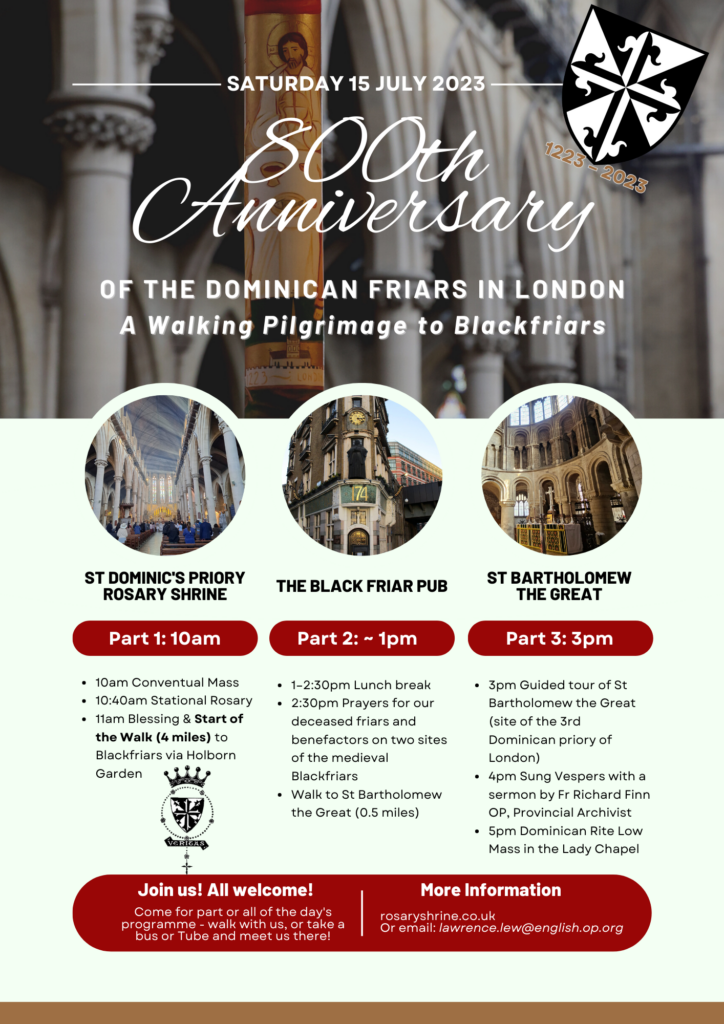

Saturday 15 July was such a blessed day as we celebrated the 800th anniversary of the London Dominicans, walking some 15,000 steps to the City of London, and praying at the 4 locations where we’ve praised, blessed, and preached the Gospel since 1223. We began with Conventual Mass in St Dominic’s, and Fr Lawrence remarked in his sermon that this year also marks the 140th anniversary of its completion and the 100th year since it was consecrated.

Our expectations were exceeded in several ways: Over 120 people walked the 4-mile-journey with us, and around 200 joined us at the end for Vespers at the Priory Church of St Bartholomew the Great in Smithfield; thunderstorms had been forecast but a blast of rain after the morning Mass was dispelled as we prayed the Rosary in the church, and the rest of the day was windy but fine and sunny at times.

Thank you to all who joined us, prayed with us, and helped and supported us. Above all, we thank God and Our Lady and St Dominic for a wonderful day.

To view a PDF of the booklet which contained the prayers and hymns and history of the places we visited, and the people we prayed for, click this link: 800th walk.

Below is the text of the sermon preached during Vespers by Fr Richard Finn OP, Provincial Archivist and author of a new history of the English Dominicans.

How are we to know what the God of peace desires of us? To know his will for us in the circumstances of our changing world? And how, as the Letter to the Hebrews has it, do we become what is acceptable to Him? Such questions are pressing in every age. For them to be answered, the apostolic faith handed down from generation to generation must be preached afresh for each generation to hear, interrogate, and respond. St Augustine once imagined Jesus knocking loudly on the door of a contemplative’s cell and saying to the startled contemplative: “Open to me, preach to others. How shall I have access to people who have actually shut their door to me, if no one opens the door? How shall they listen to me, if no one preaches?”

Eight hundred years ago members of the English royal court thought they had perhaps found the right preachers for their generation. They established a tentative alliance with a small band of Dominican friars who had newly arrived in England. King Henry III and his justiciar, Hubert de Burgh, quickly saw how these skilled expositors of Sacred Scripture could preach and minister to the king’s subjects in the rapidly growing towns and cities across the country. Though the friars opened their first house at Oxford in 1221, to attract recruits among the university’s students and teachers, Hubert was soon busy with preparations for a small Dominican house at London which had opened by 1224 outside the walls on the east side of Shoe Lane, Holborn. Other members of the king’s council saw what could be done at Winchester and elsewhere.

In the decades that followed, demand for this new Order of Preachers grew, as people valued not only their sermons, but the friars’ ministry as confessors, the beauty of their chanted liturgies, and their willingness to address the moral questions thrown up in a more mercantile and urban society. The friars visited the sick, consoled the dying in their homes, and prayed for them after they had died. History should not blind us to the novelty of this extensive pastoral ministry soon shared with Franciscans, Carmelites, and other friars. With support from the nobility, civic dignitaries, and townsfolk, Dominican priories opened in towns and cities across the country; but that early alliance with the crown was also cemented as the king supported new and existing foundations, and chose close advisors and confessors from among the friars. At London, the first Dominican priory quickly proved too small for the many friars who taught or were being trained there, or who preached both there and in the surrounding district. What’s more, the church was too small for the throng of townsfolk who flocked to its services. King Edward I supported his Dominican archbishop of Canterbury, Robert Kilwardby, and his Dominican confessor, John of Darlington, in moving the friars after 1275 to a vast new monastic complex at Ludgate where the River Fleet joined the Thames.

Under Henry VIII, a long and fruitful alliance abruptly ended as every religious house in the kingdom was suppressed. The London Blackfriars was surrendered in November 1538. Its roofs were stripped of their lead, and the property was eventually sold off by a crown which did not want people to hear the Catholic Faith preached in its full integrity. Friars who challenged the asserted royal supremacy over the English Church got short shrift. Under Edward VI, ‘reformers’ recast a national church along increasingly Protestant lines. The tide turned briefly for five short years, from 1553 to 1558, when Mary Tudor and Cardi

nal Pole sought to re-establish Catholicism, and entrusted this former Augustinian church to a small group of English, Spanish, and Dutch Dominican

s led by a theologian and former exile William Perrin. A prominent preacher at St Paul’s cross, Perrin’s Spiritual Exercises and Ghostly Meditations would be popular reading among Catholics when they could no longer worship openly in Elizabethan England.

After Elizabeth’s eviction of the friars in 1559 it would be three centuries before the Dominicans once again had a priory in London. In penal times, a few would minister from Embassy chapels, or at one of the royal palaces when there was a Catholic king or queen. One of the finest, Fr Thomas Middleton, managed to minister widely while still technically a prisoner in the Clink. Another, the elderly Fr David Kemeys, arrested in the hysteria whipped up by Titus Oates over the supposed Popish Plot, was so weak he couldn’t stand up in the dock at his trial, and died in Newgate prison before he could be convicted. These men witness to a mission faithfully served in difficult times, and a readiness to adapt in changed circumstances.

Only in 1861 did the Dominican friars return to a new Priory in the city at Haverstock Hill. In place of their former royal and civic support, they now relied on the generosity of benefactors like Miss Helen Tasker who gave some £9,000 (then a huge sum) towards the building of St Dominic’s. By 1890 the community comprised some eleven priests and seven lay brothers. While some clergy served the local parish, others took advantage of the new railways to serve as mission preachers up and down the land. They might hear up to a thousand confessions in the course of each mission.

Where does this leave us now? Grateful, certainly, for past support, and for the fidelity shown by our predecessors in preaching the Gospel. Inspired, hopefully, to be as resourceful and adaptive as our predecessors in facing new challenges. And may the God of peace make us ready in this generation to do his will in all kinds of good action, above all in collaborating to preach the Gospel of Jesus Christ, attentive to the needs, fears, questions, and desires of our fellow men and women, now and in future generations.